Iteration in Game Design

Quickly - this is not a triumphant return - but rather a brief reprise.

I want to talk about this in the context of video games rather than tabletop games singularly because I have not touched a piece of paper or dice or anything like that in some time. All in an attempt to “shut my brain off” and not get too distracted by anything of any great depth. The way I approach the hobby is pretty heavy handed, absorbing, engrossing, and thinky, and this is totally out of line with my goals the last month or two. It is practically mandated that I not tax my mind too heavily with distraction, so any free time I have had to myself that hasn’t been filled with obligations has been spent allowing my brain to melt under the force of radioactive light.

To make a long story short I had a wild couple of weeks over the holiday. I also happened to be deeply troubled and depressed, but among the drugs and the alcohol (I’m fine now, don’t worry, it was a short-lived mania induced bender) there were also great treasures to be found. Between winning some prizes at work and a successful couple of casino runs, we had a fortuitous Christmas, and probably the most prominent gift under the Christmas tree this year was a scattering of games and the Evercade VS-R console; a quirky and cool little tribute to the “golden age” of home console gaming, the Evercade takes proprietary cartridges, typically loaded with games from either particular publishers or platforms, with quite a large selection of cartridges to choose from.

It’s been a lot of fun introducing my kids to a lot of these titles. Probably most enjoyable among them are the three Neo Geo themed cartridges, containing a decent collection of games, most significant among them being the first three Metal Slug entries, though a couple of personal picks on top of those are Magician Lord, Garou: Mark of the Wolves and Sengoku. But it was the somewhat obscure Toaplan Collection 3 that has really sparked my interest, and geared me back into a genre I have not explored for quite some time, head first: the SHMUP. And the gateway drug that started it? A little game called Batsugun, typically known as the first of the Danmaku or “bullet hell” sub genre of shooter games.

I’m not going to explain what “bullet hell” means because I have respect for my readers intelligence. Needless to say, these games have a pedigree of extreme difficulty, and satisfy a most autistic and primal instinct in me - a Terror Instinct if you will (more on that later) wherein I have a tendency to enjoy difficult, fast paced, reflex and pattern recognition intensive games.

Funny enough despite my love for tabletop RPG’s and gaming, I am just not really a fan generally speaking of the same genre when it comes to the video world. Occasionally I will pick up a game, usually something really sadistic like Wizardry because I must be a masochist. But I’ve never really craved the immersion or escapism of big sprawling adventures. In fact, to put it bluntly, I find them dull and boring and they feel like a big waste of time. I think I’ve picked up Skyrim about 17 times and put in a total playtime of about 6 hours in total trying to get into it. I just can’t. And as I get older, I crave even more short burst games where I can play them for 20 minutes and then go and do something else.

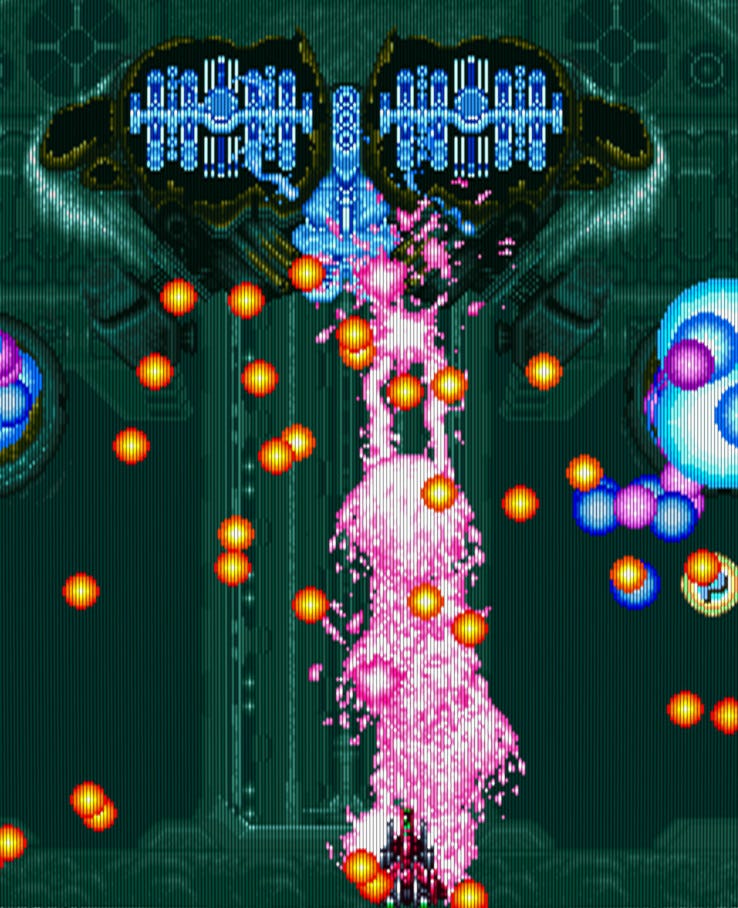

I was all over Danmaku games for a long while at some point, going so far as to import a handful of incredible games for my Xbox 360 in the genre, namely the infamous Mushihimesama Futari, and Dodonpachi Saidaioujou, both by SHMUP gods from the far east, a little company called Cave. Cave may have perfected the bullet hell, but Toaplan certainly was its birthgiver. And going through our library of Evercade titles, all the way back to the very humble beginnings of Space Invaders and R-Type has really had my gears grinding about iteration in game design.

Admittedly part of this thought process actually stemmed from one of the most detestable YouTube “personalities” in our hobby, a name so vile I dare not speak it, but one who has insisted numerous times that OSR game designers are “not real game designers”. That assertion has always been incredibly irksome to me, especially given that this individually put together what has to be the objectively worse “game” I have ever seen while having the gall to have any opinion about design.

Though I’ll give him this; his “game” is out, and AUZ still isn’t.

But I have been thinking a lot about parallels, I just don’t think it’s particularly interesting or timely to talk about it from the tabletop perspective since video games are what I am doing right now and what sparked this topic in my mind. I do, infact, think OSR game designers are “game designers”, because they engage in all the elements of game design, whether or not they are working on top of an established framework. The implication that iteration does not constitute design is baffling to me, and if I were to apply that to the SHMUP genre, it would mean that ever game after R-Type or Gradius that scrolled horizontally is not a real game because those games also scroll horizontally and therefore, anything after that does the same is a copycat.

It’s a frankly insane leap in logic, but that is essentially the claim. And it really is fascinating to see just how far these different genres of games have come through iterative design and years of refinement.

The Danmaku to me is the ultimate, distilled form of expressing the essential gameplay loop of a SHMUP. You have deceptively simple principles at work in this genre. There are things that keep appearing on the screen in front of and around you. Those things usually kill you when they hit you, and they shoot other things at you that you have to be careful to avoid. But if you do not prioritize enemy types and attempt to clear enemies from the screen in a timely fashion, the screen gets progressively more cluttered with things that will make you die.

So the general thought process of playing these games is peripheral vision around your ship, understanding how big the “hitbox” on your ship is, (what part of the ship is actually vulnerable to collision with enemies or projectiles) prioritizing and focusing fire on critically dangerous blobs of enemies as they appear on the screen to minimize their bullet output, and knowing when escape is impossible and when to expend a power up such as a bomb to save your skin. There are other considerations as well depending on the varying mechanics the game offers, but these elements are typically present in the vast majority of both vertical and horizontal scrolling space shooters.

The bullet hell takes these elements and amplifies them to their maximum possible extreme. In many of them, you will often see bullets filling up half or three quarters of the screen real-estate as you are weaving through pixel wide blank spots among the neon colored chaos. Your own weapons are usually absurdly powerful, often taking up the width of half or more of the screen as you unleash streams of electric death before you like some starship wielding god of destruction. Many of these games have an “autobomb” feature where, when a bullet grazes your hitbox, a bomb is automatically dropped from your manifest to clear the playfield for you, helping you to live another precious few seconds in order to achieve the coveted single credit run - all for the lonely gratification of sheer will and perseverance, and maybe if you are lucky, a brief “like” on a Discord post from others who are wasting their time in the exact same manner.

It’s not even a matter of refinement really, because if refinement were all that was going on, we would have never moved away from single screen games like Space Invaders. But the interesting thing is that adding elements such as scrolling, bombs, complex enemy patterns - none of these invalidate the various styles that came before. There are still single screen shooters, rare though they might be. There are still shooters that are effectively SHMUP oriented where the screen is manually scrolled by the player who has to move against the tide such as in Outzone, Guerilla War, Shock Troopers, and Ikari Warriors. Then there are games like Herzog Zwei which take those fundamental shooting and scrolling elements and expand them into a more cohesive and persistent landscape but also added the earliest elements of the real time strategy genre, and the interesting thing is that these all co-exist in the same fundamental landscape, but have forked off in multiple directions, with each of those individual paths being iterated on further and further, creating new forks, and distilling others in the same way Danmaku games have.

This has happened in other places as well, and I think how we go from the simplicity of Space War, Asteroids, and Space Invaders to the utter insanity of Battle Geregga, Dodonpachi Daioujou, and Mushihimesama is through increasing player mastery over these games, and the increasing demand by diehards for progressively more challenging experiences.

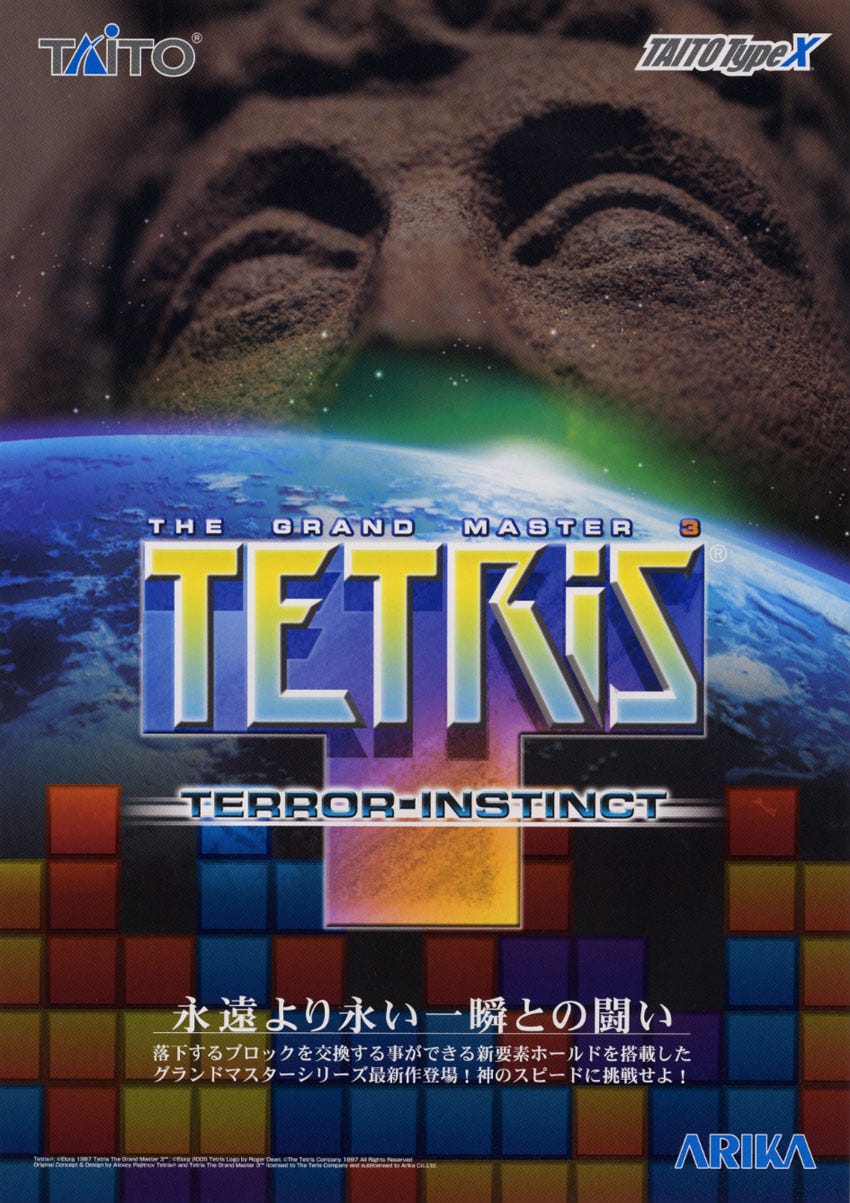

I was pleased to find out just yesterday, having for the first time in my life a decent and PC/Xbox compatible joystick, that in the last couple of years a sequel was finally produce to one of my favorite franchises in history. Not only the franchise itself, but to a particularly demanding and little known branch outside of the arcade scene in Japan.

Tetris The Grandmaster 3: Terror Instinct is a coveted game in the longrunning Tetris franchise. A follow up to Tetris The Grandmaster 1 and 2 by Arika, it has never been released outside of the arcade in North America in any official capacity. One look at some of its more difficult challenges exemplifies why.

At the “end” of Tetris on the NES, once you reach a certain score threshold, the game lauds you as a “Tetris Master”. This means very little because the requirements to achieve such a feat are infinitesimally low in the demand they place on the player. But Tetris is also the kind of game that has absolutely tremendous skill gaps among the hierarchy of its worldspanning player base. To seven year old Compleat DM, I could have never imagined seeing one of the ending screens of Tetris. 25 year old Compleat DM on the other hand would be completely ashamed to get anything less than two or three hundred thousand points by the end of a run, and that is barely scratching the surface of the greatest achievements in the game, which go far beyond achieving a maximum score value, right down to achieving things not even previously thought possible until over 30 years of time was put in to the game to see just how far it could be pushed, right to the point where the game itself completely breaks under the weight of such a feat. For all intents and purposes, NES Tetris has been mastered, but it was also not designed with that insanely high level of skill in mind.

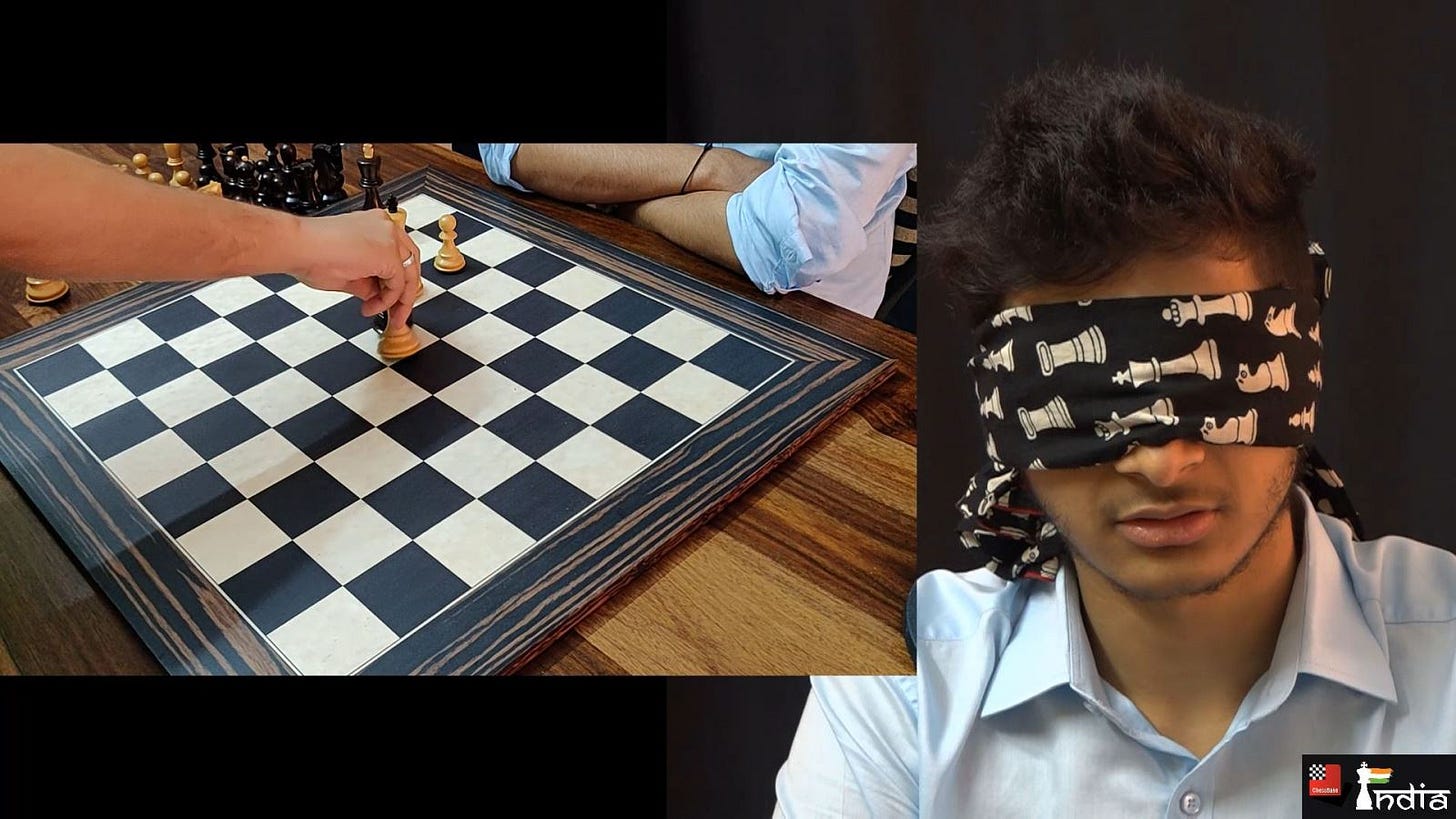

That’s really where the Grandmaster series came into play. It introduced concepts that were novel at the time of its release. It contained an intensive grading system, where to actually be labeled a “Grandmaster” by the metric of the game required players to be mechanically perfect in their execution to the point of requiring them to quite literally survive a round of “blind” play, where there are not even blocks present on the screen, and players are expected to play without any visual reference to what is happening. This to me is on the same level of blind Chess, and is a feat that has been accomplished by an exceedingly small number of people, most of who had to invest no small amount of money for actual arcade hardware in their own home in order to be eligible to even attempt it before ways were found to emulate the game on PC.

As such, and with so many modern and feature full versions of Tetris at hand that are squarely aimed at the general market, the demand for something like Tetris Grandmaster is exceedingly low, so to see that they have actually made a fourth iteration of the series and that it is available on Steam is fascinating because it’s hard to imagine it achieving any kind of financial success. The bullet hell genre certainly struggles with this as well.

But again, this is where iteration comes in. Tetris was a pretty unforgiving experience on both the Gameboy and NES. The randomization of pieces would often be a truly hellish thing to witness when playing the game at high speeds, and building a perfect tower in wait for a “longbar”, the simple four square line that makes getting a “Tetris”, where you clear four lines at once, even possible. I have played thousands of games of Tetris, perhaps tens of thousands, and I can’t tell you how common it is to be completely starved of longbars when you need them most.

This was recognized as a frustration, and later versions of Tetris universally used a “bag” system of randomization, wherein there is an invisible bag with each individual piece. Once this bag is emptied, it is filled again, and the process repeats, meaning you will never experience a starvation for the right piece. This simplification made it possible to master the fundamentals far easier, and created wiggle room to expand on other, perhaps unintentional elements of the design, such as the “T Spin”, where you can spin a small piece to fill a gap that is not accessible through normal play. In addition to this came the ability to hold a piece and swap it out for another less desirable one, and the ability to slide a piece along the top of a tower in progress for a time so that it could be repositioned, rather than it locking in place immediately after making contact with another.

So you can see where “problems” were identified, ironed out, and how that gave rise to new innovation in the series. Being able to slide pieces came from the game becoming so fast, that it was not humanly possible to move a piece to the far left or right of the screen with any consistency by all but the best players who understood frame inputs and other technicalities. It meant a game of Tetris could feel far more intense and stressful while in reality, it was actually significantly easier despite far faster falling speeds, to the point that in games like Grandmaster, and now many other games in the series, pieces don’t even drop from the top once a new one is given to the player; they simply immediately manifest at the top of the tower, and have to be manipulated into position from there in a short amount of time.

While Grandmaster is the ultimate expression of challenge and difficulty, and meant to be unconquerable by only the smallest select elite Tetris players, some of its innovations have moved into the mainline series for a different purpose, which is simply to provide a more engaging and addictive experience. In the end, everyone benefits although the vast majority will never even hear about the Grandmaster games, let alone have the balls or the time to sit there and slog through in an attempt to acquire the coveted Grandmaster title.

And here is where we finally get to the part that most of you probably give two shits about - how does this apply to the tabletop hobby?

There is a big push in some of the social spaces of this hobby for the superiority of more simulationist/wargaming/hardcore D&D. The rhetoric is that these are ultimately vastly better experiences. I can’t sit and pick that apart too much because that has very much been my own lived experience over the last few years as well. But I have long since abandoned furious adherence to D&D as an “ideal”. To the point where I'm not even sure why I ever cared about how other people played in the first place. I still play Space Invaders, R-Type, and Sonic Wings despite the fact that there are not ten thousand projectiles in my face. Though to be fair, R-Type doesn’t need that to be one of the most tremendous pain in the ass video games I’ve ever experienced regardless. I know what I like, you go ahead and like whatever you like. My approach here is always about design, and I can’t dismiss other types of games in good faith even if they aren’t my personal bag.

But either way, to see the iteration of these games as they have progressed is very reflective of what I have been talking about. The tabletop roleplaying game itself is a fork of wargaming, which itself was comprised of many many different forks, and the RPG itself has forked yet more down a multitude of paths. And iterations made down one fork can affect another, and vice versa. Shadowdark is a prime example of a game that is essentially an amalgamation of the best of the more hardcore OSR while retaining the quality of life features of more modern D&D while also introducing its own curiosities. I think to do this process justice would require a lot more time than I’m willing to give a single article as it’s long enough already, but this has been explored a lot in this space. So my interest in writing this was more in the comparison, because I do think that despite fundamental differences, the processes of design and iteration present with some fascinating similarity between the digital and the tabletop world of gaming.

Before I end, part of me wants to elaborate on what has been going on in my life for context. But I only want to do this where it actually applies to the relevance of this blog. So I will be putting out another article that does exactly this before going dark for awhile longer.

Apart from being an excellent article, this was worth a like for the Monty Python image at the top